Copper Is Not as Simple as We Pretend: High-Current Degradation at Short Time Scales

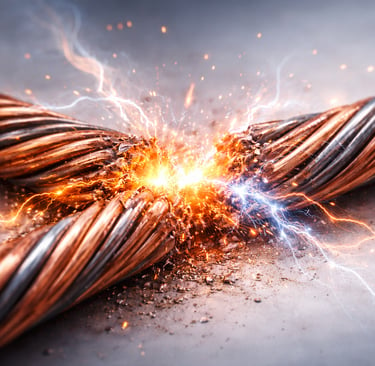

Copper is usually treated as a solved, linear material. Under high current densities and fast transients, that assumption fails. This post examines how resistivity, heat, and microstructure evolve together at short time scales—and why copper often degrades long before melting ever occurs.

Vikram Kaushik

1/29/20263 min read

Copper Is Not as Simple as We Pretend: High-Current Degradation at Short Time Scales

If power is not the limiting factor in extreme electromagnetic systems, then the obvious next question is: where does failure actually begin?

Copper is treated as a solved problem.

Its resistivity is tabulated. Its thermal conductivity is celebrated. Its behaviour is assumed to be linear, stable, and well understood. In most engineering calculations, copper appears as a constant — a passive carrier of current whose job is simply to stay out of the way.

That assumption quietly breaks down under high-current, short time-scale loading.

In pulsed power systems, fault conditions, high-density busbars, fast switching contacts, and electromagnetic launch or forming applications, copper is no longer a benign conductor. It becomes an active, evolving material whose properties change on time scales comparable to the electrical event itself. This behaviour appears repeatedly in systems that, on paper, satisfy power and temperature limits, yet fail prematurely at specific locations that models rarely prioritise.

Current Density, Not Current

Failures attributed to “high current” are almost always failures of current density.

At short time scales, current does not distribute uniformly across the conductor cross-section. Skin effects, proximity effects, contact geometry, and microstructural heterogeneity all contribute to highly localised current paths. Regions only microns wide can carry orders of magnitude higher current density than the bulk average.

In those regions, copper behaves very differently from its textbook description. This is not a marginal correction; it is a regime change. Once current localisation sets in, subsequent material response is governed by local conditions, not global averages.

Rapid Resistivity Evolution

This localisation matters because, at elevated current densities, resistivity is no longer a fixed material property.

Electron–phonon scattering intensifies rapidly with temperature, while temperature rises themselves are sharply confined in space and time. The result is a positive feedback loop:

Local current concentration → rapid local heating → increased resistivity → further current crowding.

At microsecond and sub-microsecond time scales, this evolution unfolds before any meaningful thermal diffusion or macroscopic equilibrium can occur. Classical steady-state thermal assumptions cease to be valid not because they are wrong, but because the system never enters the regime in which they apply.

Microstructure Starts to Matter

Once electrical and thermal responses are tightly coupled in time, microstructure can no longer be treated as background detail.

Under conventional operating conditions, grain boundaries, inclusions, surface roughness, residual stresses, and oxide films are often treated as second-order effects. Under high current density and short pulses, they become dominant.

Grain boundaries act as preferential scattering sites. Surface asperities distort current flow. Small variations in contact pressure or oxide thickness redirect current into narrow filaments. Features that would normally average out instead define where damage initiates. What was once statistical noise becomes the controlling variable in failure.

Damage Without Melting

One of the most persistent misconceptions in discussions of copper conductors is that failure coincides with melting.

In reality, irreversible degradation often accumulates well below the melting point. Localised annealing, void formation, electromigration-like transport, surface evaporation, and interfacial breakdown can all occur without any obvious macroscopic change. Electrical integrity and dimensional stability are frequently lost long before liquid copper is observed.

By the time melting is visible, the failure mode has already been selected. Melting is not the cause. It is the post-mortem signature.

Why This Matters

Design margins based on bulk temperature rise or average current density provide a false sense of security in extreme regimes. Copper conductors that appear massively overdesigned on paper can fail because the relevant physics is unfolding at smaller length scales and shorter time scales than the model assumes.

Treating copper as “simple” is convenient. Treating it as inert under fast transients is dangerous.

As systems push toward higher peak currents and faster electrical events, copper must be treated not merely as a conductor, but as a material whose electrical, thermal, and microstructural states evolve together in time. Ignoring that coupling is no longer conservative—it is an implicit assumption that the most fragile parts of the system do not matter.

They usually do.